Temperature Pioneers: On the Shoulders of Giants

The history of thermometry is a story of discoveries, errors, and groundbreaking insights. It begins with the first attempts of antiquity to understand heat and cold, leads through the ingenious simplicity of Galileo Galilei’s thermoscope, to the high-precision Standard Platinum Resistance Thermometers (SPRTs) of our time.

Every advancement in the history of thermometry builds upon the knowledge and experiments of scientists who researched before us. Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit, Anders Celsius, William Thomson (Lord Kelvin), and many others not only developed temperature scales but revolutionized our understanding of heat and energy. Without their ideas and measurement methods, reliable temperature measurement would be unthinkable today.

We stand on the shoulders of these “temperature pioneers”. Their work shapes not only today’s science but also our modern life. I will take you on a journey through the history of thermometry – from the first simple experiments of the past to the high-precision temperature measurement of the present.

Introduction – History of Thermometry

Temperature is one of the most important physical quantities in our everyday lives. Without precise temperature measurement, many things would be more complicated or even dangerous. But this wasn’t always the case. For centuries, people had no way to measure temperature accurately. It was only with the development of the first thermometers in the 16th and 17th centuries that a new era of science and technology began. How have thermometers evolved over time? What milestones have brought temperature measurement to today’s level of precision?

Inhalt

Why is Temperature Measurement Important?

Temperature influences our daily lives more than we often consciously perceive. From reaching for a jacket in the morning to brewing the perfect coffee to controlling the heating in winter – without precise temperature measurement, many things would be impractical or even dangerous.

Even in the kitchen, temperature plays a crucial role. When cooking or baking, it determines taste and consistency. A steak is only perfect when the right core temperature is reached, and chocolate melts at body temperature – which is why it melts so pleasantly on the tongue. Coffee also only tastes really good when it’s hot enough, but not so hot that it burns your tongue.

Temperature is important not only in preparation but also in food storage. A refrigerator must be cold enough to keep food fresh, but not so cold that fruits and vegetables freeze.

In healthcare, temperature measurement is indispensable. When we have a fever, a thermometer immediately gives us an assessment of whether it’s a harmless cold or possibly a more serious illness.

A quick glance at the thermometer often determines how we dress or what activities we pursue. If it’s frosty outside, we dress warmly; in high temperatures, we opt for light clothing. Temperature is also crucial for our safety in road traffic: black ice can form when temperatures are below freezing.

Ultimately, temperature measurement is an invisible helper that makes our lives safer, more comfortable, and healthier. Whether at breakfast, at work, or on the street – it determines many decisions without us consciously noticing.

Brief Preview of the History of Thermometry

The history of temperature measurement goes back a long way. Even in antiquity, scholars tried to understand heat and cold, but it wasn’t until the 16th and 17th centuries that the first measurable scales were created. Around 1593, Galileo Galilei developed the first thermoscope, which made temperature changes visible, but didn’t yet provide precise values. In the 18th century, researchers like Fahrenheit, Celsius, and Réaumur introduced precise temperature scales that laid the foundation for modern measurement methods. With the industrial revolution came new technologies such as the mercury thermometer, electrical resistance thermometers, and later digital sensors.

Today, the International Temperature Scale of 1990 (ITS-90) enables highly precise and globally uniform temperature measurement. It is based on defined fixed points, including the triple point of water (0.01 °C).

In high-precision measurement, Standard Platinum Resistance Thermometers (SPRTs) are used, allowing measurements with accuracy in the microkelvin range.

The history of thermometry shows how simple observations evolved into a scientific standard.

Early Attempts at Temperature Measurement

Before thermometers existed, people had to estimate temperature differences in simple and often subjective ways. In ancient times, there were no scales or accurate measurement methods, but various cultures developed methods to roughly evaluate heat and cold.

The Simplest Method: Feeling with the Hand

The most obvious way of assessing temperature was by touch. People held their hands in the sun, in water, or in the wind to feel heat or cold. However, this method is prone to error – our skin quickly adapts to temperatures, so we often only perceive relative differences.

Air Expansion as an Early Temperature Indicator

Even in ancient times, scholars observed that air expands when heated and contracts when cooled. Although no specific individuals are recorded by name as having made this observation, early scientists used this principle to develop simple devices based on air expansion.

Medical Significance: The Temperature of the Body

In ancient medicine, temperature played an important role in the history of thermometry. The Greek physician Hippocrates (ca. 460–370 BC) recommended assessing a patient’s temperature by touching their forehead or hands. This was an early form of diagnosis still used in medicine today – even though we now have fever thermometers.

While the methods of antiquity were rudimentary, they laid the foundation for later developments. The observation of air expansion later led to the development of the thermoscope, and medical temperature assessment showed how important thermometry is for everyday life.

First Theoretical Considerations in Antiquity (e.g., by Philosophers such as Empedocles or Aristotle)

Long before thermometers existed, ancient philosophers dealt with the concepts of heat and cold. Since they did not yet have physical measurement methods, they interpreted temperature based on natural phenomena and philosophical principles. Two of the most significant thinkers in this field were Empedocles (5th century BC) and Aristotle (4th century BC), whose ideas influenced scientific thinking for centuries.

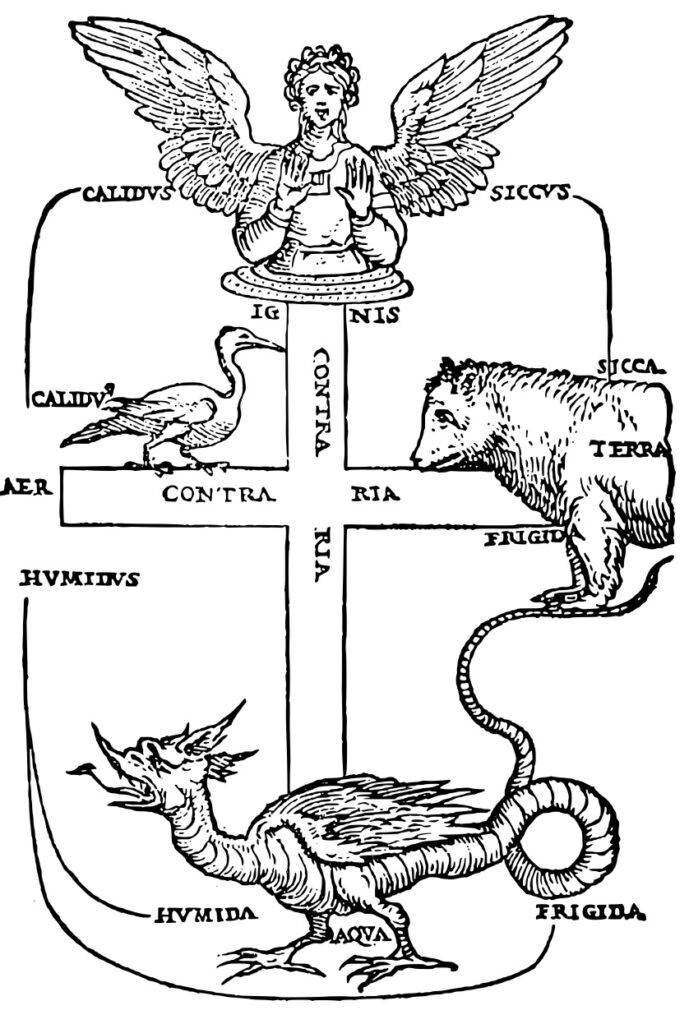

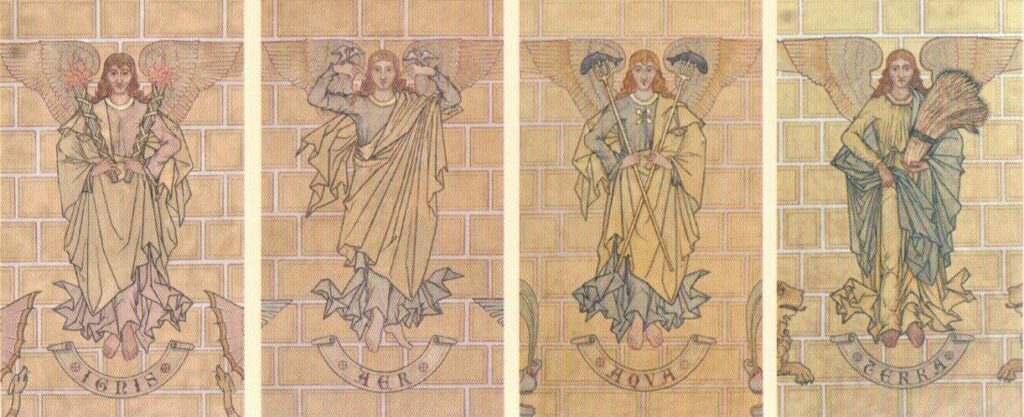

Empedocles: The Four Elements Theory and Temperature as a Property of Matter

In the history of thermometry, Empedocles was one of the first philosophers who attempted to explain nature through fundamental elements. He developed the four-element theory, according to which everything consists of the four basic substances: fire, water, air, and earth. Heat was associated with fire and air, while cold was linked to water and earth. According to this theory, temperature was not an independent physical quantity, but a property of the elements themselves.

This approach was used as a basis for natural sciences for centuries. It wasn’t until much later that it was recognized that temperature depends not on the four elements, but on the movement of molecules – a concept that was only developed in modern times through the kinetic theory of gases.

Aristotle: Heat as the Counterpart to Cold

Aristotle expanded on the ideas of Empedocles and proposed a model in which heat and cold acted as opposing principles. He believed that each material naturally possessed a certain “natural heat” or “natural cold” that could be altered by external influences. According to Aristotle, heat was associated with rising (e.g., hot air or flames), while cold led to condensation and cooling.

Aristotle assigned specific properties to the four elements:

• Fire: hot and dry

• Water: cold and wet

• Earth: cold and dry

• Air: hot and wet

These associations formed the basis for his understanding of heat and cold as fundamental properties of matter.

These ideas continued to be used in medicine, alchemy, and natural philosophy for centuries in the history of thermometry. Especially in the humoral medicine of Hippocrates and Galen, temperature played a major role – it was believed that the balance of “hot” and “cold” fluids in the body determined health.

From Philosophy to Measurement Science

Although ancient theories in the history of thermometry did not yet allow precise measurements, they laid the foundation for the scientific understanding of temperature. The idea that heat and cold are natural, measurable quantities eventually led to the development of the first temperature measuring devices in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Today we know that temperature is a result of the movement of atoms and molecules – a concept that has little to do with ancient notions. Nevertheless, the realization remains in the history of thermometry that philosophers tried to systematically explain temperature over 2000 years ago.

The Invention of the First Thermometers

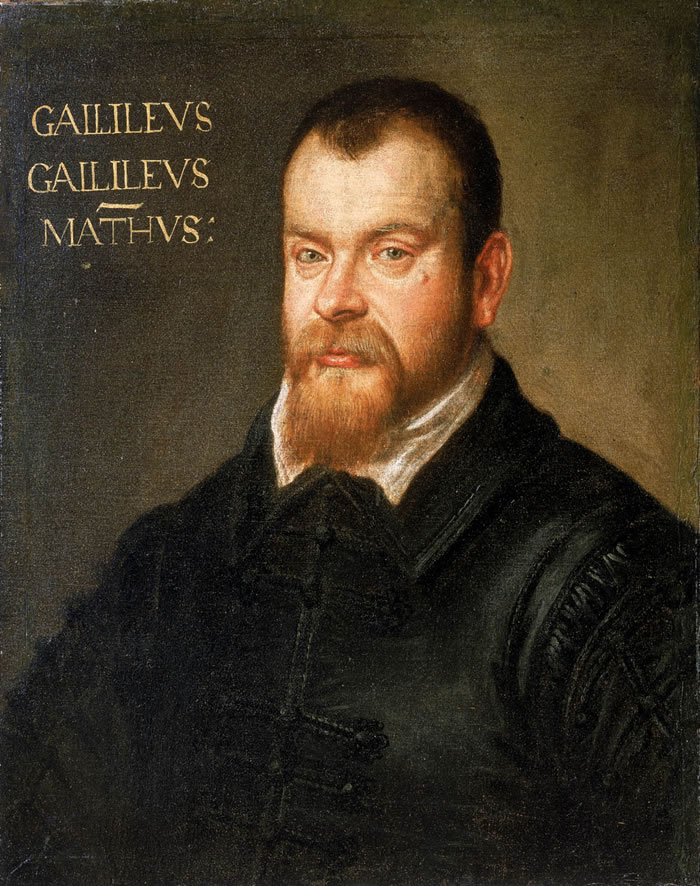

The 16th Century – Galileo Galilei and the Thermoscope (ca. 1593)

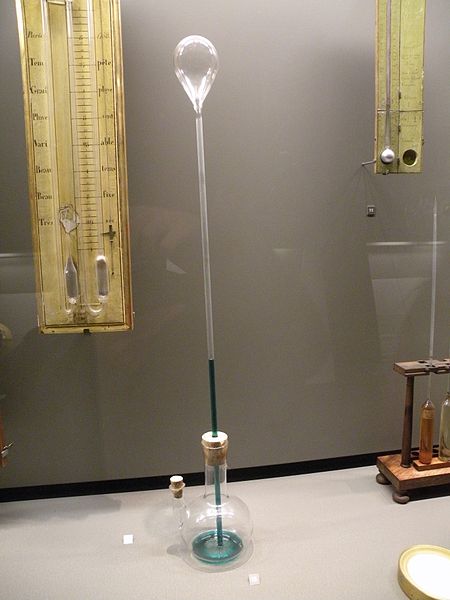

In the late 16th century, the systematic exploration of temperature measurement began in the history of thermometry. One of the first significant developments was the thermoscope, attributed to Galileo Galilei (ca. 1593). In fact, the exact authorship is disputed, as other scientists like Giambattista della Porta described similar devices. However, it is certain that Galilei further developed the concept and first used it for physical observations.

The thermoscope was a simple device that could make temperature changes visible. It consisted of a glass bulb filled with air, connected to a water container through a narrow tube. As the air in the bulb warmed, it expanded and pushed the water in the tube downwards. As the air cooled, it contracted and the water rose again. While this allowed for the first qualitative observation of temperature changes in the history of thermometry, it lacked a uniform scale to determine precise measurements.

A major problem with the thermoscope was that it responded not only to temperature but also to changes in air pressure. This dependency made accurate measurements difficult and later led to the development of thermometers using liquids like alcohol or mercury, which functioned independently of ambient pressure.

Despite these limitations, the thermoscope was a significant milestone. It laid the foundation for later developments in thermometry and inspired scientists like Santorio Santorio, who was the first to attach a scale to numerically capture temperature differences. Thus, the thermoscope was the first attempt to systematically visualize temperature changes.

The 17th Century – The First Scaled Thermometers by Santorio Santorio and Ferdinand II de’ Medici

In the 17th century, great progress was made in the history of thermometry. While Galileo Galilei’s thermoscope could already make temperature changes visible, it lacked a scale to obtain measurable values. Two scientists played an important role in the history of thermometry: Santorio Santorio and Ferdinand II de’ Medici.

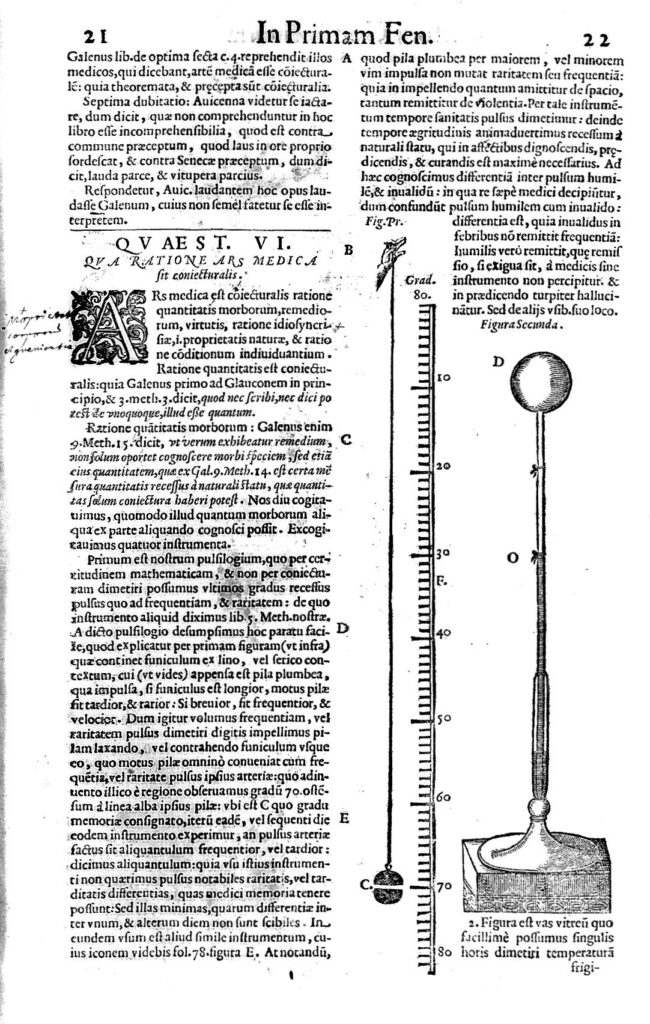

Santorio Santorio: The First Scaled Thermometer (ca. 1612)

The Italian physician and scientist Santorio Santorio (1561–1636) was one of the first in the history of thermometry to develop a thermometer with a scale. Santorio was known for his work in medical measurement technology and combined the principle of the thermoscope with a numerical scale to enable objective temperature comparisons.

His thermometer consisted of a glass tube filled with alcohol that was equipped with a scale. However, it was not yet completely independent of air pressure, so fluctuations in the environment could influence the measurement results. Nevertheless, it was a decisive advancement as it allowed, for the first time, to quantitatively capture and compare temperature changes. Santorio used his thermometer particularly in medicine to measure body temperatures – an early precursor to the modern fever thermometer.

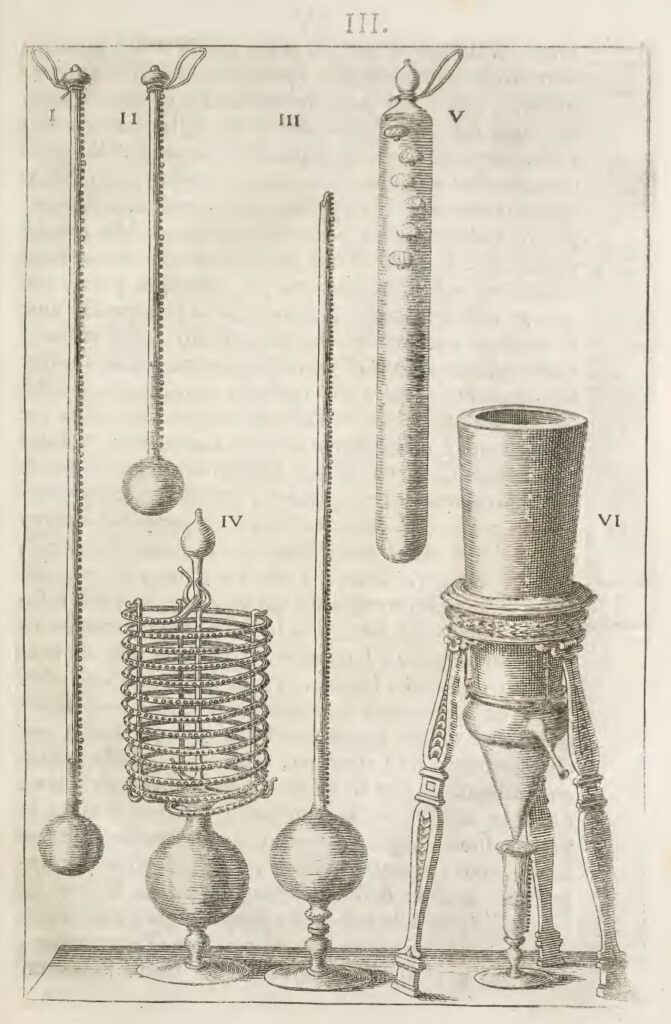

Ferdinand II de’ Medici: The First Closed Liquid Thermometer (ca. 1654)

Another major advance came from Ferdinand II de’ Medici (1610–1670), Grand Duke of Tuscany and an enthusiastic natural scientist. Under his patronage, researchers at the Accademia del Cimento developed a thermometer that used alcohol or wine as the measuring liquid.

The special feature of this thermometer was that, compared to earlier devices, it had a sealed capillary, making it less influenced by air pressure fluctuations. It thus represented an important step in the history of thermometry towards the development of stable temperature scales.

The Medici thermometers laid the foundation for the later work of Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit, who invented the mercury thermometer in the 18th century.

The works of Santorio Santorio and Ferdinand II de’ Medici marked a first turning point in the history of temperature measurement.

The first scaled thermometer by Santorio and the improved liquid thermometer that was less affected by air pressure paved the way for later temperature scales and the development of more precise measuring instruments.

History of Thermometry: First Temperature Scales

With the development of the first thermometers in the 17th century, the need to make temperature measurements comparable arose in the history of thermometry. Without a uniform scale, temperature readings were purely relative and dependent on individual measuring instruments. The first attempts to define a temperature scale came from various scientists who used different reference points.

Ole Rømer and the First Documented Temperature Scale (1701)

The Danish astronomer and physicist Ole Rømer (1644–1710) was one of the first to develop a systematic temperature scale. His scale set the freezing point of water at 7.5° and the boiling point at 60°. This made temperature measurements reproducible for the first time.

However, Rømer’s scale had some disadvantages: The choice of his fixed points was arbitrary, and the division was not particularly practical. Nevertheless, it was an important step towards standardizing temperature measurement.

Isaac Newton’s Temperature Scale (1701)

Almost simultaneously, Isaac Newton (1643–1727) proposed a temperature scale that was more oriented towards practical experiences.

Instead of using absolute fixed points such as the freezing or boiling point of water, Newton, for the first time in the history of thermometry, oriented himself to everyday temperature phenomena and assigned them values on a scale. Among his approximately 20 scale points were “cold air in winter” as a low reference point and “glowing coals in the kitchen fire” as an upper fixed point.

Later, Newton set the temperature of melting snow (0°) as a reference point and measured other temperatures relative to it based on the expansion of mercury.

Newton’s scale was primarily intended for scientific purposes and was later replaced by more precise scales. Nevertheless, it was important on the path to modern thermometry.

Development of Uniform Temperature Scales

The Foundations for More Precise Scales

The early temperature scales were not yet universally standardized. Different researchers used different fixed points, and many scales were based on subjective empirical values. Scales, such as those by Ole Rømer (1701) or Isaac Newton (1701), were in development. As thermometry advanced in the 18th century, it became clear that a uniform temperature scale was necessary in the history of thermometry.

It wasn’t until the 18th century that scientists like Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit, Anders Celsius, and René Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur succeeded in developing generally accepted scales that eventually became the basis for modern temperature measurement.

Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit (1724) – Mercury Thermometer and Fahrenheit Scale

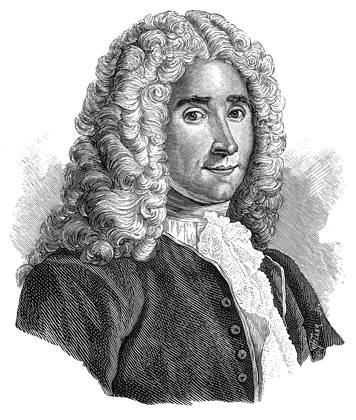

In 1724, the German physicist Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit (1686–1736) introduced one of the first standardized temperature scales, which is still used today in countries such as the USA. In addition to the scale, he also developed the first reliable mercury thermometer, which allowed for more accurate measurements than earlier alcohol thermometers.

The Mercury Thermometer – More Precise Measurements

Fahrenheit initially experimented with alcohol thermometers but found that alcohol freezes at low temperatures and expands unevenly at higher temperatures. Therefore, he began using mercury as a measuring liquid.

The Advantages of Mercury:

- Remains liquid over a wide temperature range (-39 °C to 357 °C).

- Expands linearly, allowing for more accurate measurements.

- Does not evaporate easily, which extends the lifespan of the thermometer.

With these properties, the mercury thermometer became the standard method for temperature measurements in science and technology.

The Fahrenheit Scale – Three Fixed Points for Temperature Measurements

Fahrenheit established three fixed points for his temperature scale:

- 0 °F: The lowest temperature he could produce with a mixture of ice, water, and ammonium chloride

- 32 °F: Freezing point of water

- 96 °F: Body temperature of a “healthy person”

- 212 °F: Boiling point of water

These fixed points allowed for a reproducible scale that functioned independently of individual thermometers.

The Fahrenheit scale quickly gained acceptance in England and the British colonies but was replaced by the Celsius scale in most countries during the 19th and 20th centuries. Today, it is used almost exclusively in the United States.

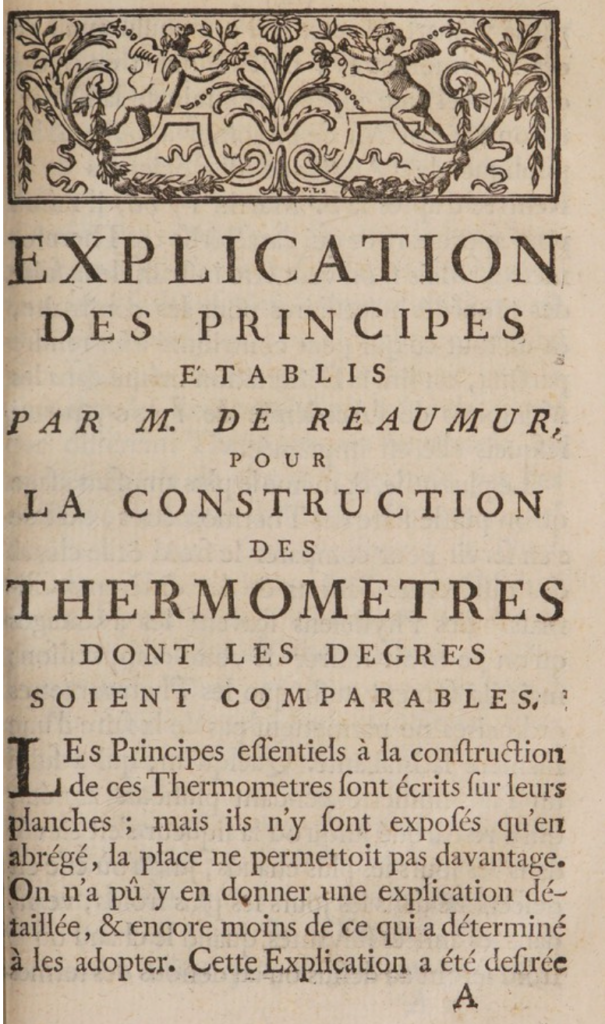

The Réaumur Scale (1730)

The French scientist René Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur (1683–1757) developed a temperature scale for alcohol thermometers in 1730, which was used for a long time in France and parts of Europe.

Characteristics of the Réaumur Scale

- 0 °Ré: Freezing point of water

- 80 °Ré: Boiling point of water

Réaumur chose a division into 80 degrees, as he assumed that alcohol expands linearly with temperature. However, this assumption proved to be inaccurate, as liquids expand differently at various temperatures.

The Réaumur scale was primarily used in France, Italy, and Russia, but lost significance in the history of thermometry with the introduction of the Celsius scale.

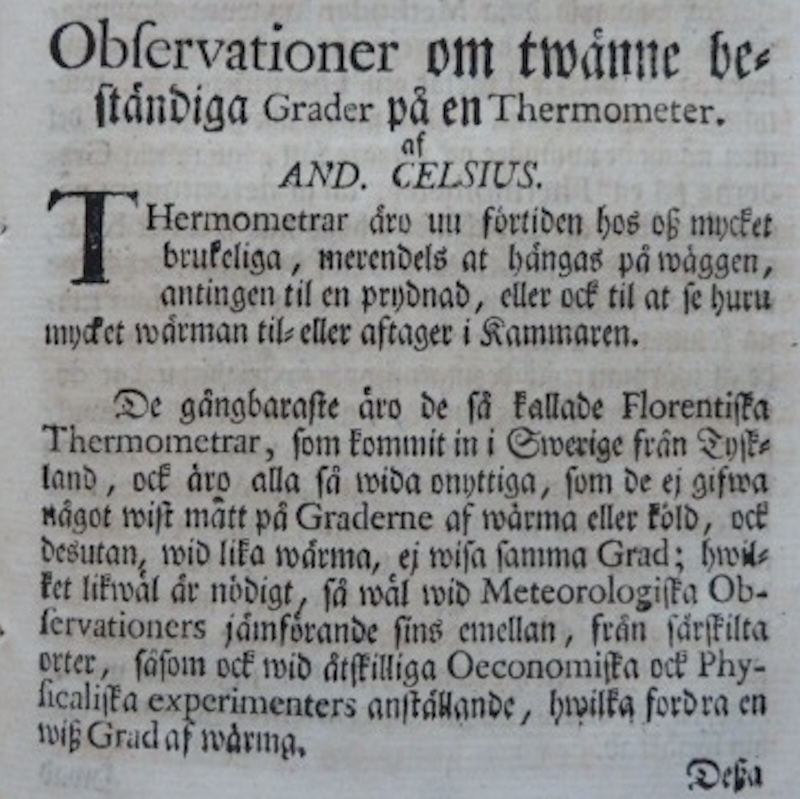

Anders Celsius (1742) – Celsius Scale

The Swedish astronomer and physicist Anders Celsius (1701–1744) developed a new temperature scale in 1742 that later became established as an international standard. Unlike the Fahrenheit scale, Celsius used a decimal division, which allowed for intuitive handling.

The Celsius Scale

In his work Observationer om twänne beständiga grader på en thermometer, Celsius proposed a temperature scale with two fixed points at normal pressure:

- 0 °C: The boiling point of water.

- 100 °C: The freezing point of water.

This inverted scaling was initially unusual. After Celsius’ death in 1744, his students, particularly Carl von Linné (1707–1778), advocated for a reversal of the scale – a special process in the history of thermometry. This set the freezing point at 0 °C and the boiling point at 100 °C – a more intuitive order that became established worldwide.

Advantages of the Celsius Scale

The Celsius scale had two major advantages over earlier temperature scales:

- Easy handling: The decimal division into 100 steps facilitated measurements and calculations.

- Precise fixed points: The scale was based on the physical properties of water (at normal pressure), which were reproducible everywhere.

Celsius Scale and Its Current Significance

Today, the Celsius scale, known as degrees Celsius (°C), is one of the most widely used temperature scales and is used as the standard for temperature measurements in almost all countries. Only in the USA and a few other countries is the Fahrenheit scale still used.

The Celsius scale also forms the basis for the Kelvin scale (K), which is used in science. The relationship is:

0 °C = 273.15 K (Kelvin begins at absolute zero).

The introduction of the Celsius scale was another major step in thermometry. Due to its simple division, clear fixed points, and intuitive handling, it quickly became the international standard. Although Anders Celsius himself did not live to see the current scaling, his work is among the most important developments in the history of temperature measurement.

The Kelvin Scale (1848)

In 1848, the Scottish physicist William Thomson, Lord Kelvin (1824–1907) introduced the first absolute temperature scale. A significant step in the history of thermometry! The Kelvin scale (K) is based on the absolute zero, the lowest possible temperature value at which all thermal motion ceases. The Kelvin scale (1848) is the first scientifically based absolute temperature scale.

Characteristics of the Kelvin Scale:

- 0 K: Absolute zero (-273.15 °C).

- 273.15 K: Freezing point of water (0 °C).

- 373.15 K: Boiling point of water (100 °C).

The Kelvin scale is particularly used in science, physics, and thermodynamics, as it is independent of specific fixed points and is based on the energy movement of particles.

The Kelvin scale is now the official temperature scale of the International System of Units (SI). A major advantage of the Kelvin scale is that it allows temperature values without negative numbers.

Advances in the 19th and 20th Centuries

With the rise of modern science and technology, the 19th and 20th centuries brought great advances in temperature measurement. New temperature scales were developed, and research focused on more precise measurement methods and new technologies.

In particular, the introduction of platinum resistance thermometry and thermocouples improved industrial and scientific temperature measurement and led to great advances in the history of thermometry.

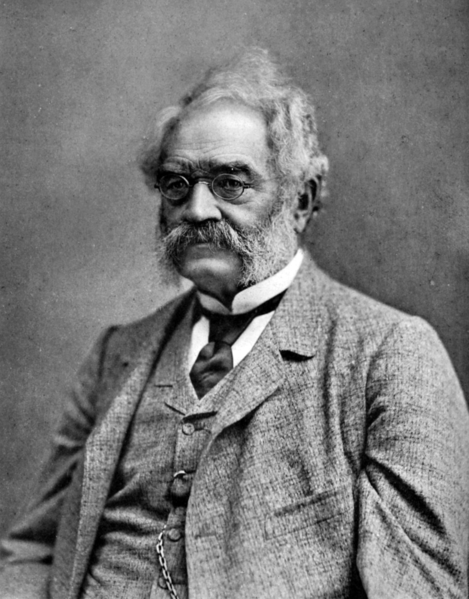

Development of Resistance Thermometers (Siemens Callendar, 1871–1887)

The introduction of electrical resistance thermometers in the late 19th century was a significant advancement in temperature measurement. While liquid thermometers had previously dominated, resistance thermometers enabled highly precise and reproducible temperature measurements for the first time. Two scientists played a central role in this development:

- Werner von Siemens (1871): First experiments with resistance thermometers based on platinum.

- Hugh Longbourne Callendar (1887): Refinement of measurement methods and introduction of platinum resistance thermometers (PRTs) for scientific applications.

Werner von Siemens (1871): First Concepts of Resistance Thermometry

The German inventor and engineer Werner von Siemens (1816–1892) was the first to recognize in 1871 that the electrical resistance of a wire changes with temperature and can be used as a measurand. He proposed using metals as temperature sensors, as their resistance increases with temperature in a predictable manner.

Siemens initially used copper and iron wires, but found that these materials were not stable enough over long periods. Therefore, he continued his development work with platinum as the resistance material.

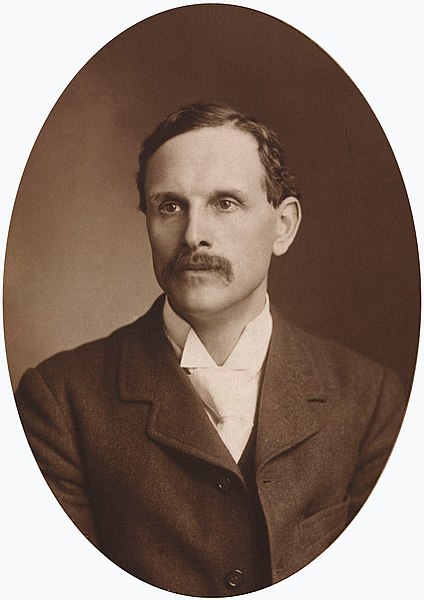

Callendar (1887): Platinum as Ideal Material for Resistance Thermometers

In 1887, the British physicist Hugh Longbourne Callendar (1863–1930) refined resistance thermometry and developed the first precise platinum resistance thermometer (PRT).

Why Platinum?

Callendar, like Werner von Siemens, found that platinum is ideal for resistance thermometers because it:

- Offers highest stability over long periods.

- Shows an almost linear resistance increase with temperature.

- Has a high melting point (1768 °C) and is suitable for wide temperature ranges.

He determined a resistance-temperature relationship and developed an empirical equation for temperature calculation:

[

R_T = R_0 (1 + α T)

]

where:

- ( R_T ) is the resistance at temperature ( T ),

- ( R_0 ) is the resistance at 0 °C,

- ( α ) is the temperature coefficient of platinum.

This equation was the first standardized approach to electrical temperature measurement and later became the basis for platinum resistance thermometers (PRTs).

The Callendar-Van Dusen equation (CvD equation) extends the original empirical formula by Hugh Callendar and describes the nonlinear resistance-temperature relationship of platinum resistance thermometers (PRTs) in the range of -200 °C to 850 °C, enabling high-precision temperature measurements. This step is of great importance in the history of thermometry, as the so-called Callendar-Van-Dusen equation is still used today.

From Callendar’s Thermometer to Modern Resistance Thermometry

After Callendar’s work, platinum resistance thermometers (PRTs) were further improved and later established in the International Temperature Scale (ITS-90) as Standard Platinum Resistance Thermometers (SPRTs).

Important developments in the history of thermometry:

- Introduction of protected wire windings to minimize mechanical stress.

- Improvement of long-term stability through high-purity platinum.

- Optimization of measuring bridges to precisely detect extremely small resistance changes.

Today, platinum resistance thermometers are the most accurate electrical thermometers.

Thermoelemente

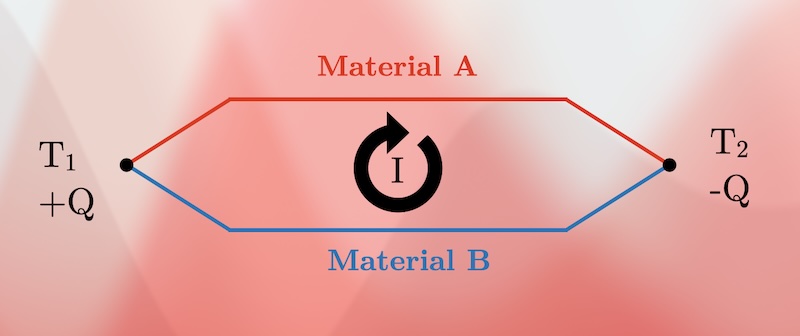

Thermocouples are one of the most versatile methods for temperature measurement and are used worldwide in industry, science, and research. They are based on the Seebeck effect, which was first discovered in the 19th century.

The Seebeck Effect – Foundation of Thermocouples

The German physicist Thomas Johann Seebeck (1770–1831) discovered in 1821 that an electric voltage is generated in a closed circuit made of two different metals when the two contact points have different temperatures. This phenomenon is known as the Seebeck effect and forms the basis for thermocouples.

Principle:

- A thermocouple consists of two different metals (often alloys) that are connected at both ends.

- One connection (measuring point) is heated or cooled, while the other remains at a reference temperature (called thermocouple reference junction or cold junction).

- The temperature difference creates an electric voltage that directly correlates with the temperature. This voltage is called thermoelectric voltage.

Development and Standardization of Thermocouples

After Seebeck’s discovery, the technology was further developed:

- 1826: Jean Charles Athanase Peltier discovered the reverse effect (Peltier effect), which shows that electric currents can generate temperature differences.

- 20th century: Thermocouples were standardized and optimized for industrial applications. Today, thermocouples are standardized according to international norms, e.g. IEC 60584 and IEC 62460.

Common Thermocouple Types and Their Properties

| Type | + Leg | – Leg | Measuring Range in °C |

| T | Cu | CuNi | -270 … 400 |

| J | Fe | CuNi | -210 … 1200 |

| E | NiCr | CuNi | -270 … 1000 |

| K | NiCr | Ni | -270 … 1372 |

| N | NiCrSi | NiSi | -200 … 1200 |

| R | Pt13Rh | Pt | -50 … 1768 |

| S | Pt10Rh | Pt | -50 … 1768 |

| B | Pt30Rh | Pt6Rh | 0 … 1820 |

| C | W5Re | W26Re | 0 … 2315 |

| A | W5Re | W20Re | 0 … 2500 |

| Cf. DIN EN 60584-1:2014-07 | |||

Advantages and Disadvantages of Thermocouples

Advantages:

✔️ Very wide temperature range (from -270 °C to 1820 °C).

✔️ Robust construction, resistant to vibrations and mechanical stress.

✔️ Fast response time to temperature changes.

✔️ No external power supply required (self-powered through Seebeck effect).

Disadvantages:

❌ Lower accuracy than resistance thermometers (SPRTs, PRTs).

❌ Thermoelectric voltage is not linear – calibration or correction tables required.

❌ Electromagnetic interference can affect the signal.

Thermocouples are a cost-effective, robust, and versatile method for temperature measurement and have proven themselves in numerous industrial and scientific applications. Although they do not achieve the precision of resistance thermometers or SPRTs, they are popular due to their low cost, wide range of applications, and high temperature ranges.

International Temperature Scales

To enable globally consistent temperature measurements, various international temperature scales have been developed over the years. While early measurement methods were often based on individual scales, it became necessary in the history of thermometry to create a unified reference.

As early as the 19th century, initial attempts were made to base temperature scales on fixed thermodynamic points.

International Hydrogen Scale (1887)

The International Hydrogen Scale was introduced in 1887 and was one of the first attempts to establish a uniform temperature scale on a fundamental physical basis. It was based on the properties of a gas thermometer operated with hydrogen as the measuring gas.

The Hydrogen Scale used a constant volume gas thermometer that determined the temperature based on the pressure change of hydrogen at constant volume. The basis was Gay-Lussac’s law, which states that the pressure of an ideal gas at constant volume changes linearly with temperature.

International Temperature Scale of 1927 (ITS-27)

The International Temperature Scale of 1927 (ITS-27) was the first officially defined temperature scale introduced as a global standard for precise temperature measurements.

The introduction of the ITS-27 by the International Committee for Weights and Measures (CIPM) was intended to create a uniform scale for science and technology.

The ITS-27 was based on defining temperature fixed points that were oriented on the phase transitions of pure substances.

The ITS-27 was a major advancement as it defined for the first time a globally uniform and precise temperature scale. It was widely used in scientific and industrial applications.

International Practical Temperature Scale of 1948 (IPTS-48)

The International Practical Temperature Scale of 1948 (IPTS-48) was introduced as a successor to the ITS-27 to further improve temperature measurement and adapt to new scientific findings.

Reasons for introducing IPTS-48

The ITS-27 had some weaknesses, particularly:

- Inaccuracies at low temperatures, as hydrogen gas thermometers did not behave ideally.

- Measurement deviations at high temperatures caused by radiation thermometry.

- Further development of resistance thermometers that required more accurate scaling.

With the IPTS-48, a more accurate definition of fixed points and interpolation methods was introduced.

International Practical Temperature Scale of 1968 (IPTS-68)

The International Practical Temperature Scale of 1968 (IPTS-68) was a revised version of the IPTS-48 and was introduced to further improve the accuracy of temperature measurement. It was the globally recognized temperature scale until the introduction of the ITS-90.

Improvements over IPTS-48

The IPTS-68 brought several important changes:

- New temperature fixed points, especially at very low and very high temperatures.

- Optimized interpolation methods for more accurate temperature measurements.

- Extended use of Platinum Resistance Thermometers (PRTs) for more precise temperature determination.

Disadvantages and Replacement by ITS-90

Although IPTS-68 allowed for more precise temperature measurements, there were some known issues:

- Measurement deviations in certain temperature ranges.

- Non-ideal traceability to the thermodynamic temperature scale.

- Different scaling factors that led to small discrepancies in various applications.

Due to these limitations, IPTS-68 was eventually replaced by ITS-90 in 1990, which offers better thermodynamic consistency and higher accuracy.

Modern Precision Thermometry

Temperature measurement has evolved enormously since the first thermoscopes and liquid thermometers. While earlier thermometers were often inaccurate due to external influences such as air pressure fluctuations or evaporation, modern precision thermometers allow for extremely accurate temperature determination down to the microkelvin range.

Thanks to highly developed sensors, temperatures can now be measured with a precision of up to a few millionths of a degree. The development of the International Temperature Scale (ITS-90) has also created a unified reference system for high-precision temperature measurements.

Standard Platinum Resistance Thermometers (SPRTs) are the most precise resistance thermometers and form the primary interpolation instrument of the International Temperature Scale of 1990 (ITS-90), enabling highly accurate temperature measurements from -200 °C to 961.78 °C.

International Temperature Scale (ITS-90)

The International Temperature Scale of 1990 (ITS-90) is the globally recognized reference for high-precision temperature measurements. It was introduced by the International Committee for Weights and Measures (CIPM) and replaces earlier scales such as the IPTS-68 (International Practical Temperature Scale of 1968). The ITS-90 serves as a practical realization of the thermodynamic temperature scale by establishing a series of defining fixed points for precise temperature determination.

With the ITS-90, Standard Platinum Resistance Thermometers (SPRTs) were established as the interpolation instrument in the range from 13.8033 K (triple point of hydrogen) to 961.78 °C (freezing point of silver).

The ITS-90 is the most precise and internationally standardized temperature scale and is used in many fields. It represents the current international standard for precise temperature measurements. Through its temperature fixed points and interpolation instruments, it enables globally uniform and reproducible temperature determination.

Temperature Fixed Points of the ITS-90

| No. | T90 in K | t90 in °C | Substance | Representation |

| 1 | 3 to 5 | -270 to -268.15 | He | VP |

| 2 | 13,8033 | -259,3467 | H2 | TP |

| 3* | approx. 17 | approx. 256.15 | H2 | VP |

| 4* | approx. 20.3 | approx. 252.85 | H2 | VP |

| 5 | 24,5561 | -248,5939 | Ne | TP |

| 6 | 54,3584 | -218,7916 | O2 | TP |

| 7 | 83,8058 | -189,3442 | Ar | TP |

| 8 | 234,3156 | -38,8344 | Hg | TP |

| 9 | 273,15 | 0,01 | H2O | TP |

| 10 | 302,9146 | 29,7646 | Ga | MP |

| 11 | 429,7485 | 156,5985 | In | FP |

| 12 | 505,078 | 231,928 | Sn | FP |

| 13 | 692,677 | 419,527 | Zn | FP |

| 14 | 933,473 | 660,323 | Al | FP |

| 15 | 1234,93 | 961,78 | Ag | FP |

| 16 | 1337,33 | 1064,18 | Au | FP |

| 17 | 1357,77 | 1084,62 | Cu | FP |

| Walter Blanke: The International Temperature Scale of 1990: ITS-90VP = Vapor Pressure TP = Triple Point MP = Melting Point FP = Freezing Point * = Multiple temperatures are available | ||||

High-End SPRT Precision Measurement – John P. Tavener and the Copper Fixed Point SPRT

Based on the work of John P. Tavener (1942-2020), the development of a new Standard Platinum Resistance Thermometer (SPRT) for the copper temperature fixed point (1084.62 °C) represents a preliminary pinnacle in the history of thermometry. Previous SPRTs were limited to the silver fixed point (961.78 °C) due to problems with material stability and contamination at higher temperatures. Tavener solved this problem by using a synthetic sapphire carrier for the platinum winding and an alumina protection tube supplied with a slight overpressure of oxygen. This prevents the penetration of impurities and ensures a stable oxidation environment necessary for platinum. Additionally, the thermometer was equipped with a +9V DC bias to improve insulation properties and actively repel ionic impurities through an electric field.

Tests over several hundred hours at temperatures up to 1090 °C showed exceptional long-term stability with a drift of only 0.1 mK/h. While earlier attempts with sapphire protection tubes failed due to thermal stresses, this new design demonstrated unprecedented reproducibility and is thus suitable for characterizing copper temperature fixed point cells with previously unattainable measurement uncertainty.

With the development of this high-precision SPRT for the copper fixed point, the history of thermometry reaches a preliminary pinnacle – from antiquity through the first simple thermoscopes to modern precision thermometry, which today enables temperature measurements with unprecedented accuracy.

Quellen

Heron of Alexandria – Wikipedia https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heron_von_Alexandria

PubMed. (1997). Historical aspects of temperature measurement in medicine – https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9290139/

Four Elements Theory – Wikipedia https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vier-Elemente-Lehre

StudySmarter – Empedocles Elements – https://www.studysmarter.de/schule/griechisch/griechische-philosophie-theorie/empedokles-elemente/

Chemie.de – Four Elements Theory – https://www.chemie.de/lexikon/Vier-Elemente-Lehre.html

Viviani, V. (1654). Historical Account of the Life of Mr. Galileo Galilei

The Invention of the Thermometer and Its Development in the 17th Century – Burckhardt, Fritz – Basel, 1867

Museo Galileo – Thermoscope – https://catalogue.museogalileo.it/object/Thermoscope.html

Bigotti, F. – The Weight of the Air: Santorio’s Thermometers and the Early History of Medical Quantification Reconsidered – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6407691/

Wikipedia. – Santorio Santorio – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Santorio_Santorio

Accademia del Cimento. (1667) – Saggi di Naturali Esperienze

Middleton, W. E. K. (1966) – A History of the Thermometer and Its Use in Meteorology

Newton, (1701) – Scala graduum Caloris – Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society

Fahrenheit, D. G. (1724) – Experimenta et Observationes de Congelatione Aquae – Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society.

Réaumur, R. A. F. (1730). Observations sur la Construction des Thermomètres

Celsius, A. (1742) – Observationer om twänne beständiga grader på en thermometer – Kungliga Svenska Vetenskapsakademiens Handlingar.

Thomson, W. (1848) – On an Absolute Thermometric Scale – Philosophical Magazine

Siemens, W. (1871) – On the increase of resistance in conductors with rise of temperature – Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society

Callendar, H. L. (1887) – On the Practical Measurement of Temperature – Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society.

Seebeck, T. J. (1821) – On the Magnetic Polarization of Metals and Ores by Temperature Differences

IEC 60584-1:2013 – Thermocouples – Part 1: EMF Specifications and Tolerances

Bureau International des Poids et Mesures (BIPM) (1948) – Report on the International Practical Temperature Scale of 1948

Bureau International des Poids et Mesures (BIPM) (1968) – International Practical Temperature Scale of 1968

Preston-Thomas, H. (1990) – The International Temperature Scale of 1990 (ITS-90) – Metrologia, 27(1), 3–10.

BIPM. (2018). Guide to the Realization of the ITS-90.

Tavener, J. P. (2014) – A New Thermometer for the Copper Point – National Physical Laboratory

Tavener, J. P. (2013) – Further Investigations into the Performance of Copper Point Standard Resistance Thermometers – Tempmeko 2013

Image Rights

“Four Elements of Alchemy”, public domain, available on Wikimedia Commons

“The Four Elements” in the Königslutter Imperial Cathedral – August von Essenwein (1831-1892); Adolf Quensen (1851-1911), Public domain, photographed by Rabanus Flavus, Wikimedia Commons, February 15, 2012

Portrait of Galileo Galilei, painted by Domenico Tintoretto (1602–1607), photo from the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, available on Wikimedia Commons

Photo of Galileo Galilei’s thermoscope in the Musée des Arts et Métiers, taken by Chatsam, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 – available on Wikimedia Commons

Santorio Santorio – Commentaria in primam Fen primi libri Canonis Avicennae – Apud Jacobum Sarcinam, 1626 – Public Domain Mark

Medici Thermometer – Accademia del Cimento. (1667) – Saggi di Naturali Esperienze

Portrait of Sir Isaac Newton, English School, ca. 1715–1720 – Wikimedia Commons

Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit, ca. 17th to 18th Century – Wikimedia Commons

Réaumur, R. A. F. (1730). Observations sur la Construction des Thermomètres

Portrait of René-Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur from “Galerie des naturalistes” by Jules Pizzetta, 1893 – available on Wikimedia Commons

Portrait of Anders Celsius painted by Olof Arenius – Wikimedia Commons

Celsius, A. (1742) – Observationer om twänne beständiga grader på en thermometer – Kungliga Svenska Vetenskapsakademiens Handlingar.

Portrait of William Thomson – 1st Baron Kelvin – 1906 – Wikimedia Commons

Portrait of Werner von Siemens photographed by Giacomo Brogi – Wikimedia Commons

Portrait of Hugh Longbourne Callendar – circa 1900 – unknown photographer – public domain – via Wikimedia Commons

Portrait of Thomas Johann Seebeck – early 19th century, depicted in “Goethe and His World” by Hans Wahl and Anton Kippenberg – 1932 – Wikimedia Commons